The Trouble With Traditional Stool Testing

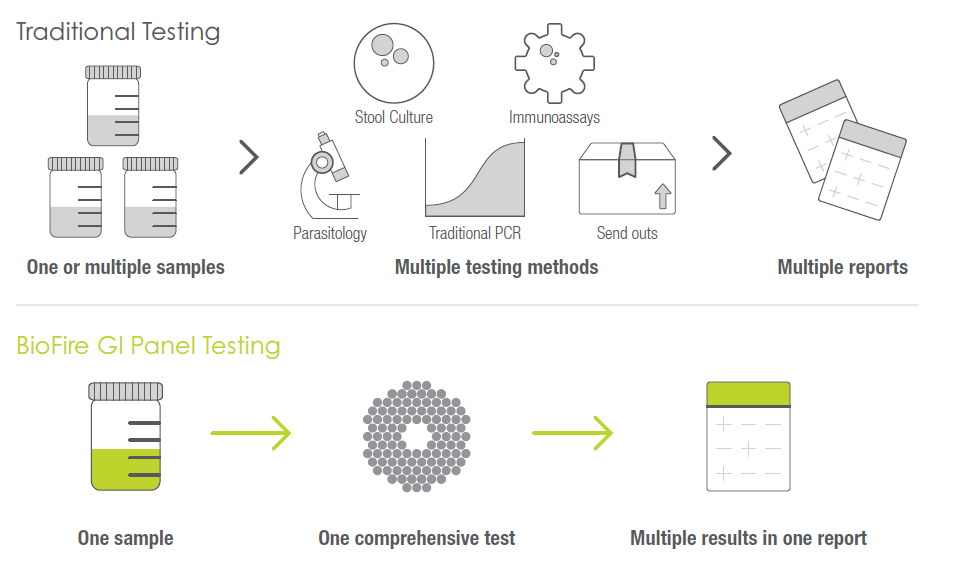

Clinicians and laboratories have a variety of methods to choose from when testing for enteric pathogens. Each of these methods comes with unique challenges and tradeoffs.

Stool culture, for instance, is a high-complexity test that can take days for results. And in the end, with a yield of only 1.5%-2.9%, it doesn’t often provide actionable answers.3

If parasites are suspected, an ova and parasite exam may be ordered. But this high-complexity test has a relatively low sensitivity and a low yield of about 1.4%.7 Due to its low yield, the test may need to be repeated, requiring additional patient samples. Furthermore, enzyme immunoassays (EIA) or direct fluorescent immunoassays (DFA) test for specific pathogens or a limited range of pathogens. These moderate-sensitivity and low-yield methods may lead to serial testing in an effort to pinpoint the probable causative pathogen.

Traditional PCR is a high-complexity test that requires a specialized laboratory. Like immunoassays, traditional PCR can test for individual pathogens or a limited range of pathogens. While results may be available within hours, traditional PCR also offers a relatively low diagnostic yield compared to multiplex testing.8

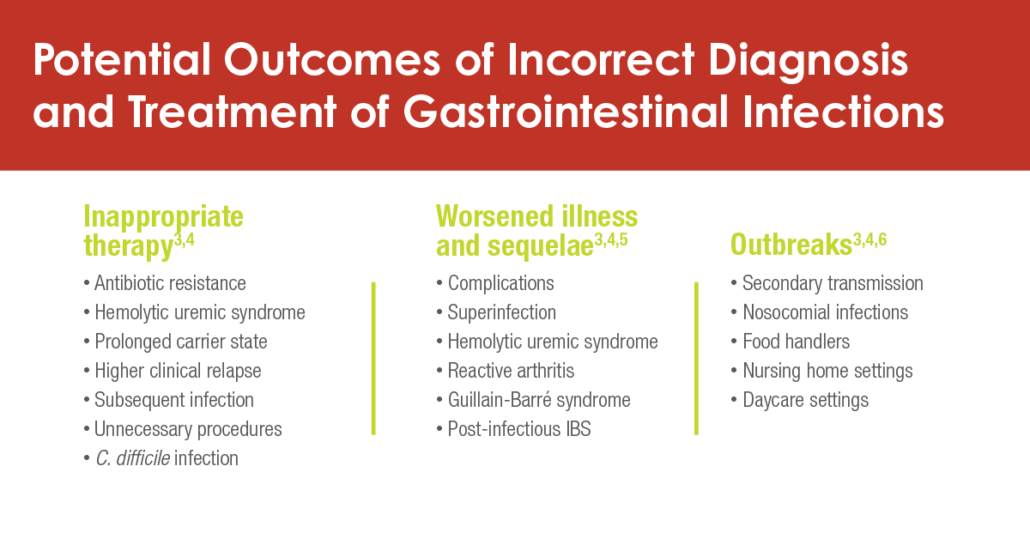

For laboratories, traditional stool testing is time consuming and usually needs to be performed by laboratorians with technical expertise. For clinicians, the lengthy time-to-result for traditional testing methods, combined with low yield and a potential need for serial testing, often forces them to make treatment decisions without laboratory results.

What does all of this mean for patients? With traditional testing, patients may experience longer lengths of stay, additional diagnostic procedures, unnecessary antibiotics, and prolonged treatment. And in the end, they may be left with continuing uncertainty about what’s actually making them sick.