How Epidemiology Began with a London Water Pump

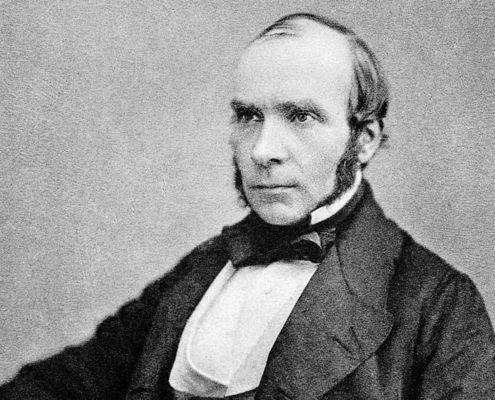

In 1854, a physician removed the handle from a public water pump—and it changed the world. Known as the father of epidemiology, John Snow was credited with ending a cholera outbreak in London.

When hundreds of Soho residents suddenly contracted the deadly disease, Snow questioned the predominant theory that cholera was spread by polluted air. (The germ theory, which is the currently accepted scientific theory of disease, had not yet gained traction.)

Snow’s research led him to a communal water pump on Broad Street. He created a map to demonstrate how cholera cases were geographically clustered around the pump. Additionally, his survey of residents determined that people who used other pumps remained unaffected. Snow came to the conclusion that sewage, which was dumped into the River Thames or into cesspools throughout town, could be contaminating the water supply and rapidly spreading disease. He disabled the Broad Street pump by having its handle removed—and the outbreak ended.

John Snow’s research on disease transmission helped determine

that cholera is a waterborne, not airborne, infectious disease.

Soon after, the diaper of a child who had contracted cholera from another source was discovered in a leaky cesspool near the Broad Street pump. The discarded diaper had contaminated the well water with Vibrio cholerae. This discovery substantiated Snow’s research, helping prove that cholera is waterborne, not airborne.

The connection between water quality and disease contraction is crucial to modern-day epidemiology. Here at BioFire, we continue to honor John Snow by innovating solutions for infectious disease diagnostics—and by naming one of our conference rooms after him. Thanks to what Snow started, the BioFire® FilmArray® Gastrointestinal (GI) Panel can test a stool sample for Vibrio cholerae (and 21 other targets) in about an hour.